Arthur Bliss

An analysis of his early chamber works: String Quartet (1914) and Piano Quartet (1915)

By Andrew Braddock

Sir Arthur Bliss, by Mark Gertler (1932). National Portrait Gallery, London.

Introduction

Arthur Bliss (1891–1975) enjoyed a prominent career as a composer in 20th-century England. His large-scale works achieved great renown and frequent performances, as did his mature chamber compositions. Some of his early works for strings, however, remain under-performed and unrecognized. They offer a fascinating window into the early creative activities of the composer, and stand as valuable works in their own right. In the course of my doctoral research into Bliss’s Viola Sonata, I came to cherish these early works, especially for their prominent viola parts. What follows below is a historical overview and brief thematic and structural analysis of Bliss’s String Quartet (1914) and Piano Quartet (1915).

Arthur Bliss’s Chamber Music

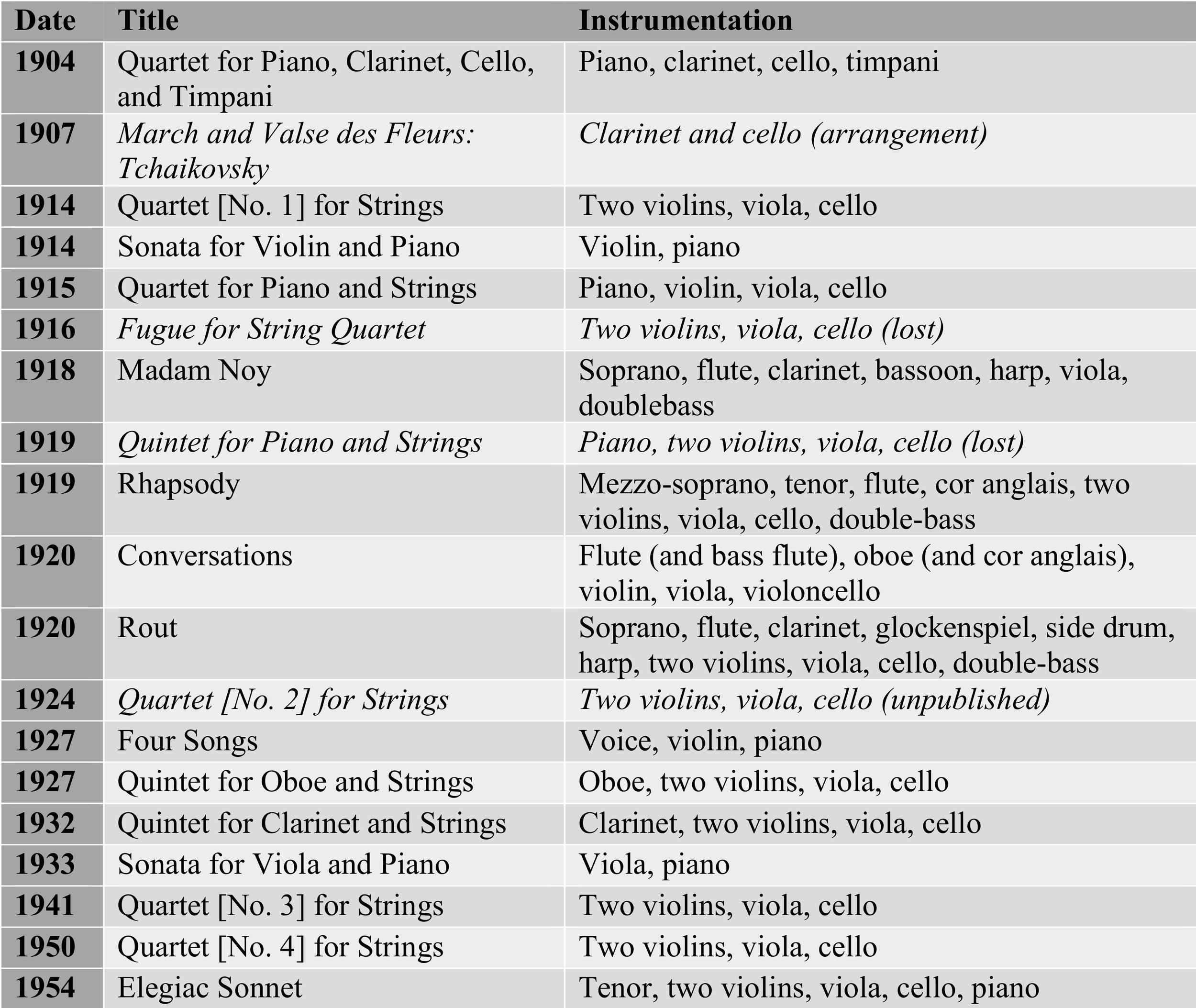

Bliss received the greatest renown for his large-scale works, most notably A Colour Symphony (1921), Morning Heroes (1930), and Metamorphic Variations (1972). Yet, although chamber music comprises a smaller portion of his oeuvre, it nevertheless appears as a consistent thread that comes to the fore at occasional and repeated points throughout his compositional career. Below is a table of all of Bliss’s chamber works for strings.

Historical Background

Upon graduating from Pembroke College, Cambridge with a BA in history and a Bachelor of Music in 1913, Bliss enrolled in the Royal Academy of Music where he studied for nearly a year before the outbreak of World War I in August 1914.

Between 1914 and 1915, Bliss completed two chamber works—the String Quartet in A major, B10 (1914) and the Piano Quartet in A minor, B13 (1915)—that were performed during the war years. The string quartet received its public premiere on June 9, 1914, in Cambridge with Howard Bliss (the composer’s brother) playing cello. The premiere of the piano quartet occurred on April 20, 1915, on the War Emergency Concert in Steinway Hall, London, with Lionel Tertis playing the viola part.

While Bliss was serving in France, his father, assisted by composer and conductor Eugene Goossens, arranged for Novello to publish both works. After the war, Bliss withdrew the unsold copies and had the plates destroyed for both works; they survived, however, in manuscript, and Edition Peters released them in 2007.

There is scant documentary evidence for Bliss’s decision to withdraw the works, but it is easy to guess why. The two works present a sunny, joyous, and un-encumbered musical world, full of piquant melodies and lightly-flowing slow movements. For a composer returning home in 1918 from multiple months-long stints on the front lines in the trenches, as one who suffered a gas attack, and whose brother had been killed in battle, this decision was undoubtedly influenced by the horrors of war he experienced and can be viewed as a renunciation of youthful naïveté.

Arthur Bliss: String Quartet [no. 1] - 1914

The three-movement string quartet features a central slow movement surrounded by two upbeat outer movements. The first movement, moderato ma tranquillo, presents a fairly straightforward sonata form (A B A` coda), with two themes in the opening A section and a rather rigidly-divided development section. The exposition and recapitulation have almost exactly the same proportions and each thematic area is separated by a four or five-measure link.

Example 1. Arthur Bliss, String Quartet [no. 1] (1914), mvt I, mm. 1–4.

The movement opens with a halting theme in A major that, despite the first note being on the downbeat of the first measure, sounds as if it begins with an anacrusis (ex. 1). Bliss develops the theme rather quickly; by the movement’s fourth phrase, the theme compresses into three-beat groupings punctuated by three concluding eighth notes that create an air of upright propriety. A general upward thrust of melodic lines gives the work a positive mood, and the lack of hard-edged cadences and chords give the opening sections a horizontally flowing lyricism. Alternations between triplet eights and dotted eighth and sixteenth figures provide just enough rhythmic variety to keep the opening section from remaining entirely stagnant. Echoes of this melodic horizontality can be heard in the opening theme in the first movement of the Viola Sonata.

The second theme (piu animato, 2/2 meter), with its half-note melodies and flowing triplets underneath, could easily be confused for music by Vaughan Williams (ex. 2). This D-natural-minor theme also exhibits the anacrusis quality found in the first theme, created by two metrical devices. The melody itself begins on the downbeat of m. 41 with the viola’s half note followed by two tied half notes. The “short-long” rhythmic quality creates a feeling of the first note leading into the next, similar to that of an anacrusis. Bliss previews this anacrusis feeling by beginning the accompanying triplets in the cello and second violin (m. 40) one measure before the viola’s melody, creating a pickup measure. The first movement of the Viola Sonata notably begins with a pickup measure in the piano before the viola’s melodic entrance.

Example 2. The flowing second theme from Arthur Bliss’s String Quartet [no. 1] (1914), mvt I, mm. 39–44.

Harmonically, the movement begins and ends in A major, but wanders through a variety of key centers, with notable stops in modally altered (mostly flattened) keys: D minor, F major and minor, C major, G minor, and F-sharp minor. Even at this gestational stage, we can see both Bliss’s commitment to tonal centers and his easy willingness to explore multiple keys within one movement. Generally speaking, this movement owes a lot of its harmonic and textural relationships to Ravel’s String Quartet (1903).

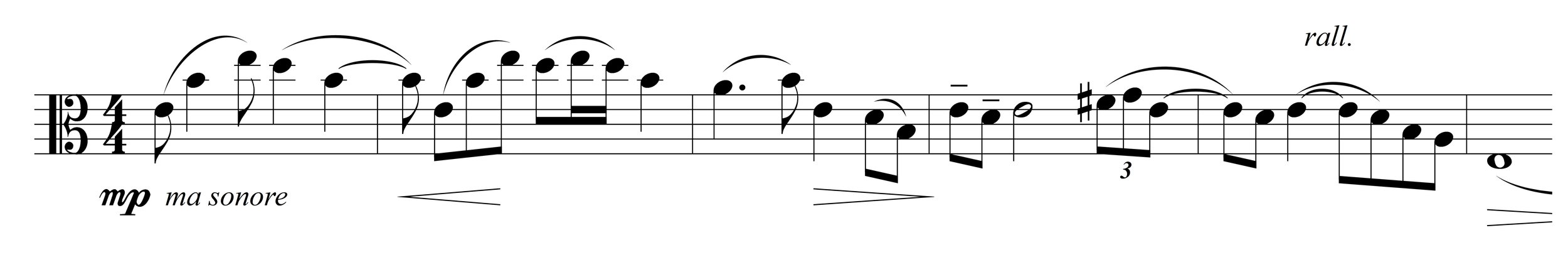

The second movement, Andante sostenuto, opens with a nine-measure unaccompanied viola solo comprised of two four-measure phrases and a single measure “coda” (ex. 3.5). Centered in the viola’s mid to lowest register, this meandering melody shifts from G natural-minor in the first phrase, to B-flat major in the second before settling again in G minor at its conclusion. Bliss retains the anacrusis feeling in this movement. But, unlike the disguised anacrusis in the first movement, the pickup note here is made explicit, beginning on the third beat of the first measure with a distinctive ascending perfect fourth from scale degree 5 to scale degree 1. With the second violin’s quasi-fugal entrance in the twelfth measure, the movement’s horizontal and linear focus becomes clear. Similar to the first movement, Bliss prioritizes horizontal melodic motion over vertical clarity.

Example 3. The viola solo opening melody from Arthur Bliss’s String Quartet [no. 1] (1914), mvt II, mm.1–11.

Bliss introduces a second thematic section—Alla minuetto, grazioso (m. 59)—that features more energetic music, enlivened by trills and dotted eighth- and sixteenth-note figures. The original melody later returns with accompanying scherzando-style staccato sixteenths, which gradually fade into more lugubrious eights. Elements of the second theme precede an eighteen-measure coda, rounding out a loosely constructed A B A B coda form. In the final cadence in the tonic key of G minor, echoes of Ravel’s style can be strongly heard. Bliss’s minor five triad (D–F–A) that resolves to a minor tonic (G–B-flat–D) in mm. 180–81 bears an almost exact resemblance in harmony and voicing to the concluding cadence in the “Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant” movement from Ravel’s ballet Ma mère l'Oye (1911; premiered in 1912). The final harmonic motion of the movement, an E-flat major triad to a G major triad (VI – I), makes for a weak and inconclusive ending. A comparable—though more harmonically complex—gesture occurs in the similarly open-ended conclusion of the Viola Sonata’s second movement. In that movement, the harmony passes from an F-sharp minor chord to a B-flat major chord, mirroring the major third root movement and the hazy ending of the String Quartet. Overall, this movement lacks much of the formal rigor and logic of the first movement, defined more by discursive ramblings rather than chiseled structure.

Example 4. Top line: viola line from String Quartet [no. 1] (1914), mvt III, mm.70–74. Bottom line: Arthur Bliss, Sonata for Viola and Piano, mvt. III, mm. 1–3

Whereas the first movement displays an impressive amount of structural coherence and motivic development from the young composer, the third and final movement suffers from an overabundance of thematic material that lacks the space for development and growth. With an almost schizophrenic parade of embryonic themes truncated by frequent multiple-measure rallentandos (five occur between mm. 38–101), the movement fails to take flight in comparison to the flowing and effusive first movement. Yet, this movement is not without its remarkable features. Bliss displays rhythmic inventiveness not seen in other parts of the quartet, including frequent hemiolas (for example, mm. 45–50) and alternations of meter that show metrical flexibility—all within a controlled context—previously unseen in the young composer’s works. With an eye towards Bliss’s future works, interjectory chorale-like chordal passages (mm. 78–81 and mm. 235–38) foreshadow the broad and expansive opening of the String Quartet no. 3 (1941). Another notable feature is the triplet repeated C’s in the viola’s lowest register, a sonority and rhythm that Bliss reuses in the third movement of the Viola Sonata.

Arthur Bliss: Piano Quartet - 1915

Example 5. Similar violin melodic passages in Bliss’s String Quartet- mvt I (Top Line), and Piano Quartet- mvt 1 (Bottom Line).

Bliss’s Piano Quartet in A minor (1915) makes for a perfect companion to his String Quartet [no. 1] as both works contain extensive similarities. In fact, many of these similarities can be more aptly identified as self-quotation. The clearest example of this can be found between the beginning of the second movement of the piano quartet to the string quartet’s opening theme. Both works have a halting beginning that features the exact same rhythm and gesture (ex. 5). The third theme in the first movement of the Piano Quartet also shares the general rhythmic structure and, more importantly, the playful character, of the two opening themes. This type of self-borrowing is frequent throughout Bliss’s oeuvre, including notable instances between the Clarinet Quintet and the Viola Sonata.

Though not as exact, another form of self-quotation can be found when comparing the initial prologue-like melody of the first movement of the Piano Quartet (ex. 6) to the opening melody in the String Quartet’s second movement. Both feature the solo viola without accompaniment, both unambiguously reside in the natural minor mode (G minor for the String Quartet, E minor for the Piano Quartet), and both begin with a pickup gesture. That Bliss chose to open two of the six movements of his early string chamber music with a melody for solo viola—and that none of the other movements have extensive solos for other instruments—suggests his particular affinity for the instrument.

Even more so than the String Quartet [no. 1], the Piano Quartet is heavily indebted to Ravel and Debussy. In fact, one passage in the first movement almost exactly recreates a moment from Ravel’s String Quartet. Bliss writes a transitional melody used in two places in the movement (mm. 80–84 and mm. 231–235) whose first five notes match exactly the rhythm and intervals of the opening melody of Ravel’s first movement.

From a general perspective, both works show a freedom and variety of key areas, frequent usage of natural minor tonality, contain a vast trove of thematic material that is developed to varying degrees, and show deep influence of Debussy and Ravel. All of these qualities are also present in the Viola Sonata, and a thorough study of these two early works pays great dividends towards understanding Bliss’s essential stylistic components.

Example 6. Opening unaccompanied viola melody from Arthur Bliss’s Piano Quartet (1915), mvt I, mm. 1-6.

© Andrew Braddock